21 November 2021 - Posted in

St. Clair Cemetery by

Father Pitt

with comments

If an illustrator wanted to draw a typical cemetery monument of the middle 1800s, it would look like this. Rich but not extravagantly ornate, these shafts were popular because they easily direct the family to the plot, and they have abundant surface for inscriptions, meaning that one expensive monument can take the place of any number of tombstones, an expense that adds up over the years as scarlet fever and cholera take their toll.

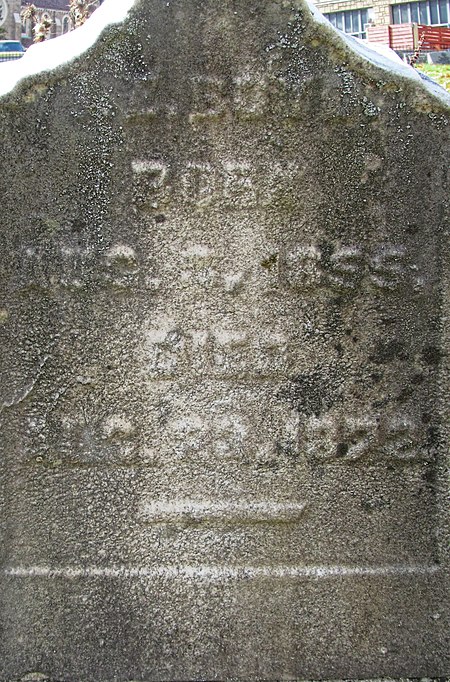

Unfortunately, the material—limestone or marble—erodes over the decades, so that the inscriptions become illegible after a while. Our readers are welcome to try their hands at reading the inscription for James M. Henry below, but poor old Pa Pitt gave up. The inscription may remember a child who was born in 1831 and died in 1837, but Father Pitt is not willing to stand by that reading.